| Applying C - Basic Arithmetic As Bit Operations |

| Written by Harry Fairhead |

| Monday, 21 December 2020 |

|

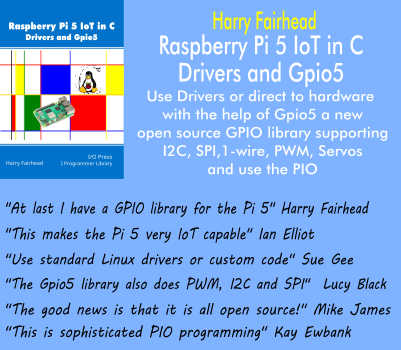

Binary arithmetic used to be well understood because you needed to know how the hardware worked - it is still important to understand it. This extract is from my book on using C in an IoT context. Now available as a paperback or ebook from Amazon.Applying C For The IoT With Linux

Also see the companion book: Fundamental C <ASIN:1871962609> <ASIN:1871962617>

Arithmetic is the forgotten task. We just expect machines to evaluate whatever expression we write and we expect it to get it right – or right enough not to cause a problem. Part of the reason for this unreasonable assumption is the availability and success of floating point arithmetic. However, even floating point arithmetic can give you results that are closer to random numbers than a valid answer if you don’t take care. This chapter isn’t about floating point arithmetic – for that see Chapter 7. Smaller computers often don’t have a hardware floating point unit and if you want to use floating point you have to use a software implementation which is slow. In most cases a better option is to use integer or fixed-point arithmetic which is more appropriate for embedded processors and special digital signal processors, for example. In this chapter we look at the basics of integer arithmetic and the next tackles its extension to fixed-point arithmetic. It is assumed that you know the basics of binary numbers, the bitwise operators and how to use hexadecimal. If you are in any doubt about these topics see: Fundamental C: Getting Closer To The Machine (ISBN: 978-1871962604) Binary Integer Addition as Bit ManipulationComputer arithmetic is almost universally done in binary. It hasn't always been this way and even today decimal representations are sometimes important, see the next section on Binary Coded Decimal, BCD. Binary integer addition is something we generally take for granted – the hardware just does it, but it can be implemented using bitwise logic and shifts, and it is instructive to do so. Addition of two bits generates a Result bit and a Carry bit:

You can see that the result is an XOR and the carry is simply an AND. This is called a half adder because it doesn’t deal with the problem of taking account of anything that might have been generated by an earlier pair of bits being added.

Can we do the same job in C without using the add operator? Addition As Bit ManipulationA half adder is easy as it is just two logical operations. If a and b are ints then: r=a^b; is the set of result bits and: c=a&b; is the set of carry bits when a and b are “half added”. For example, for a=0101 and b=0111: r= 0101 ^ 0111 = 0010 and: c= 0101 & 0111 = 0101 If you do the addition you will see that these are the result and carry bits of half adding each pair of bits without worrying about any earlier carry bits. Each of the carry bits has to be added to the result but to the next higher-order bit. In other words, we need to add the carry to the result shifted one bit to the left: a+b=r+c<<1 or: a+b= a^b + a&b<<1 This is the fundamental formula for addition but notice that it doesn’t get rid of the addition operator! To do this we have to write it in terms of the logical operators. That is, to add the result and the shifted carry we have to use: r1=r^(c<<1); c1=r & c; You can now see what the problem is – there might be another carry bit in c1 that has to be added to the result. The fact of the matter is that addition is an iteration of two logical operations and a shift, and this fact is hidden from us by its implementation in hardware. In hardware, the carry bits propagate through the full adder and it is the propagation time that is the hardware’s equivalent of the iteration. So, to compute an addition, a+b, without using the addition operator, we need to use: int ans = a;

int c = b;

int temp=0;

while (c > 0) {

temp = (ans^c);

c = (ans & c) << 1;

ans=temp;

}

The loop ends when there is no carry and if the most significant bit of the carry is set at any point then an overflow has occurred. It is worth noting that the term overflow is perhaps not the correct one. The C90 standard states that integer addition cannot overflow, it simply rolls over. That is, if a is the maximum value that can be represented, a+1 is 0. This is the wrong answer, but it isn’t necessarily an error, as we shall see. In chapter but not in this extract:

Summary

Related ArticlesRemote C/C++ Development With NetBeans Getting Started With C/C++ On The Micro:bit To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, sign up for our weekly newsletter, subscribe to the RSS feed and follow us on Twitter, Facebook or Linkedin.

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info |

| Last Updated ( Monday, 21 December 2020 ) |

A half adder takes two bits and adds them to give a result and a carry

A half adder takes two bits and adds them to give a result and a carry