| The Digital Camera |

| Written by Harry Fairhead | ||||||||||||||||

| Wednesday, 21 March 2012 | ||||||||||||||||

Page 2 of 3

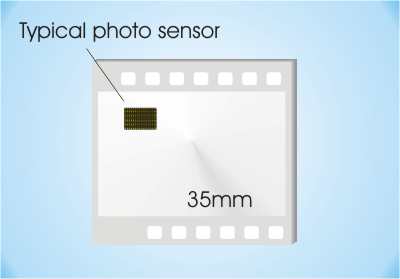

Sensor Size and Focal LengthIf you are familiar with 35mm film cameras you might have noticed that the focal lengths of typical digital camera lenses is smaller. The reason for this simply that the photo sensor is quite small compared to the size of a 35mm negative – about 1/6th of the size. What this means is that the lens that you need to create an image is quite a lot smaller in terms of focal length than is needed for a 35mm camera.

Given that photographers have become used to quoting the lengths of 35mm lenses this can cause something of a problem unless you know how they compare to a typical digital camera. The basic rule of thumb is that a lens that gives a “normal”, i.e. not wide angle and not telephoto, has a focal length about the length of the diagonal of the image so:

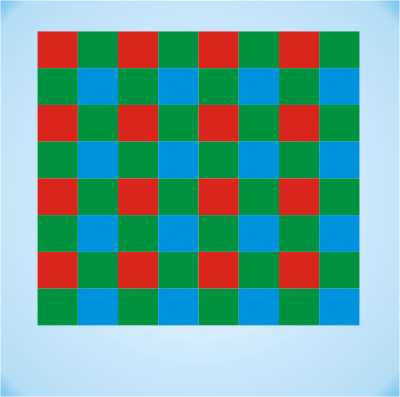

Of course this is just an approximation and it only applies top to sensors that are 1/6th of the size of a 35mm negative which applies to most camera phones. Many high end DSLRs have larger sensors which makes it possible to use 35mm lenses. While on the subject of lenses it is worth pointing out the difference between optical zoom and the cheat that is digital zoom. Optical zoom is exactly what you would expect – the lens changes focal length so increasing or decreasing the magnification of the image on the sensor. Digital zoom, on the other hand, just crops the image to a portion of the sensor – so making the image seem larger. You can achieve the same result by taking a non-zoomed image and enlarging the middle portion using a photo-editing package. Of course if you do this you lose resolution and the same happens if you use digital zoom. ExposureExposure control was a difficult job when using a film camera. You often needed to carry a separate light meter and do calculations to get the right shutter speed and aperture. If you are serious about photography you still need to take these matters into consideration but the auto-exposure programs usually do a good job. In expensive cameras there is a variable aperture which allows different amounts of light to fall on the sensor according to the scene being photographed. Usually the camera’s electronics controls the aperture to ensure that the exposure is correct. On a 35mm camera you probably have 8 or so choices for the aperture but a digital camera often only has two or three, corresponding to wide, medium and small. A DSLR camera usually has all of the apertures that you would find on a traditional film camera. The size of the aperture that you select governs not only the amount of light reaching the sensor but the “depth of field” of the lens. The depth of field is how much of the scene is in focus. A small depth of field (wide aperture) gives a sharp image of the object the camera has focused on and a blurred background and foreground. As the aperture is made smaller the depth of field increases. Of course you can’t change the aperture without altering the amount of light reaching the sensor. The usual way around this problem is to modify the exposure time. In a film camera this corresponds to how long the shutter is held open for. Most digital cameras don’t have mechanical shutters. Instead there is an electronic shutter, which simply wipes the sensor and then reads the data after a given amount of time has passed. Any "click" that you might hear from the camera is entirely a figment of the processors imagination and a loudspeaker. The mechanical aperture and electronic shutter are usually under the control of the camera’s electronics and a simple algorithm is used to select the correct aperture for the type of scene you are about to shoot. Then the exposure time is calculated according to the light that is available. If there isn’t enough light the camera will automatically fire its built-in flash. This is the reason it is important that you use any “programmed” types of photo that your camera may support. It is also worth finding out how to control the aperture and shutter speed manually to see what effects you can produce. Of course if you select a wide aperture then what you are focused on becomes more important and this is made even more complex by the fact that digital cameras autofocus. If a camera expects you to manually focus then you always think about what you are focusing on but if you have grown used to autofocus you just expect the camera to do it! ColorSo far we have only been considering a black and white sensor and most of us want a color camera. There are a number of ways dealing with this problem. We could use three sensors with a red, green and blue filter respectively. This produces good results but three sensors are expensive, power hungry, and make the camera large. As a result most cameras use a single sensor and a built-in Bayer filter pattern. Each pixel has its own tiny red, green or blue filter in a regular pattern.

A Bayer filter pattern

From this the color of an individual pixel can be computed by averaging the colors of the pixels that surround it using a process called “demosaicing”. You may notice that there are twice as many green sensitive pixels as red or blue ones. The reason for this is that the human eye is much more sensitive to shades of green than any other color and so the sensor has to be more accurate in its representation of green. Many camera companies claim to provide better color resolution by making the demosaicing algorithm more sophisticated. Generally this amounts to performing the color averaging over more pixels giving increased weight to closer pixels. |

||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated ( Wednesday, 21 March 2012 ) |