| Alan Turing's ACE |

| Written by Historian | |||

Page 1 of 2 Alan Turing is known for the "Turing Machine", but this is a theoretical device used to prove what computers can do. What is less well-known is that he designed a real physical computer - the Automatic Computing Engine at the UK's National Physical Laboratory in 1945. One of the early computing machines built in the UK, the ACE is one that should not be forgotten or overlooked. This machine was the brainchild of Alan Turing and perhaps deserves to be called a Turing machine rather more than the theoretical machine more usually given this name. Is it interesting not only because it is the product of one of the greatest of computer scientists, but because it is also a very strange machine. We tend to think that there really is only one design for a computer. Even the earliest valve-based serial computers are sufficiently like the standard Von Neumann design for us to be able to understand them and see how they fit into the overall development of hardware. The ACE is so different that it comes as something of a shock, a refreshing shock… When the Second World War ended the UK had gained considerable expertise in computing because of the code-breaking efforts based at Bletchley Park. The machine built there, Colossus, wasn't a general purpose computer even in the limited sense that the ENIAC was but it contained the elements of one. It was a digital computer custom-built to solve a particular problem. But this didn't stop the people involved in building it seeing that a general purpose machine was possible.

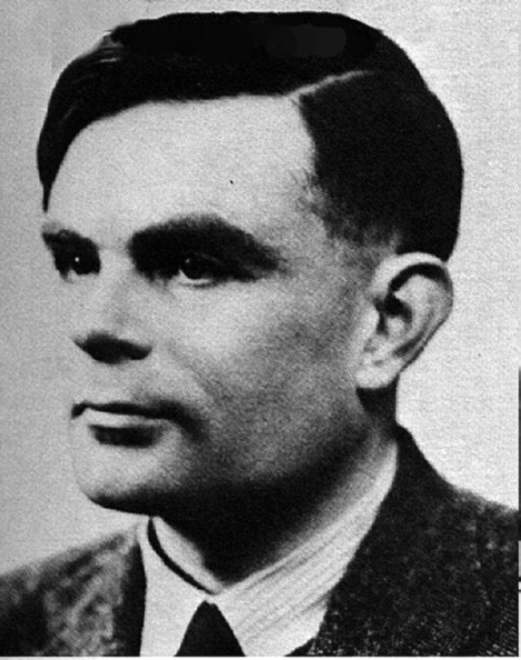

Alan Mathison Turing (1912-1954)

The Mathematics Division at the National Physics Laboratory (NPL) at Teddington was set up in 1945 and was intended to be a national centre for machine computation - the only problem was they didn't have a computer. More to the point there were no general purpose computers in the UK, but the scientists from the recently disbanded Bletchly Park thought that they could build one. Max Newman moved to Manchester University where he started the "Calculating Machine Laboratory" where the Mark I was eventually built. Flowers and Coombs, who had done much of the actual engineering, returned to the Post Office Research lab at Dollis Hill, and Alan Turing joined the new Mathematics Division at the NPL. There was some talk that a collaborative effort should be mounted to build a "national computer" but as it turned out the Post Office was too busy putting the telephone system back to rights and Manchester was busy doing its own thing. When he arrived at the NPL, Turing set to work designing a new computer. Early in 1946 he presented his paper to the executive committee of the NPL, complete with an estimate of how much it would all cost - £11,200. The then current NPL director, Charles Darwin (grandson of the originator of the theory of evolution) thought in terms of turning Turing's design into a national project. The NPL didn't really have the electronics expertise needed to build a computer on its own, although Turing had tinkered with electronics as part of the code breaking projects. Robin Addie recalls Turing at work: "His aim was to develop active elements for his computer ideas, largely NOR/AND gets etc… My vivid memories are of a man of medium build with a round head of crewcut hair bending over what we used to describe as an electrified bird's nest of resistors, capacitors and odd components insecurely fixed to a prototype chassis. All components were held aloft by little blobs of solder. At one end was a power supply delivering several hundred volts. I would watch fascinated as Turing plunged a hot soldering iron in the midst of this wonderwork. Needless to say calamities happened; sparks flew, fuses blew, and things got hot, but Turing just pressed on."

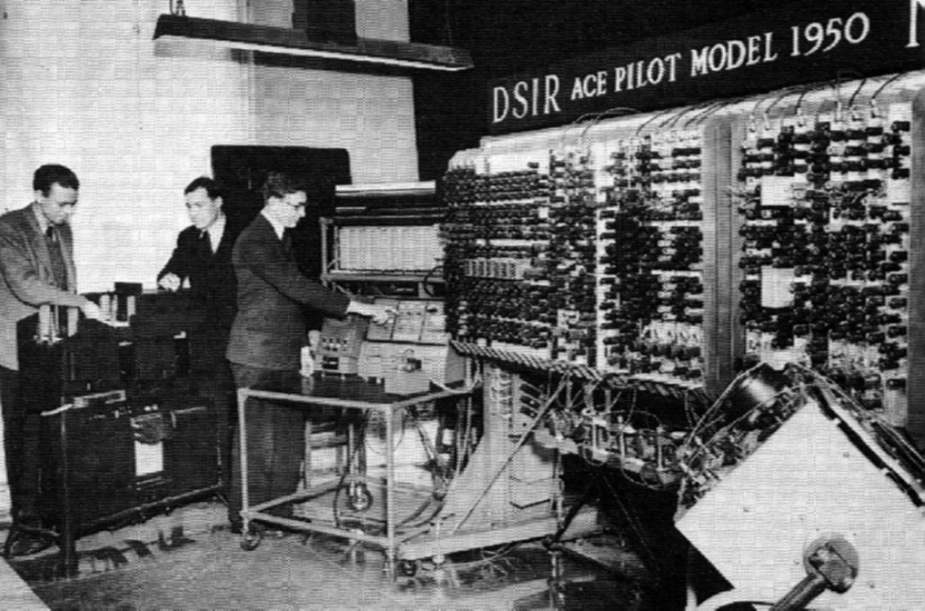

After failing to persuade anyone to collaborate with them, the NPL group, now expanded to include Mike Woodger and James H Wilkinson, continued to work on the logical design of Turing's machine that had come to be called ACE - Automatic Computing Engine. In early 1947, Harry Huskey joined the group from the USA for a year. Huskey had been involved in the engineering of the ENIAC and some of the design of the EDVAC and when nothing practical seemed to be happening he made the suggestion that they should build something. The something he had in mind was a small enough amount of hardware to pass as experimental but big enough to actually be used for some computation. Turing Moves OnTuring wasn't keen, but the rest of the group was. Turing didn't want to waste time building test machines he wanted to go straight to the real thing - as far as he was concerned it was obvious that the ACE would work. A lot of his certainty came from his experienced during the war and Colossus but, as this was still strictly classified information, he couldn't use any of this in his proposal or arguments for the ACE. The ACE test assembly, as it was called, was never finished. Work started in 1947 and after a few months Turing left to take a year’s sabbatical at Kings College Cambridge. Wilkinson took over control of the project and Turing never returned. In late 1947 Darwin decided that the mathematicians didn't know enough engineering to build the ACE. It was decided that the NPL Radio Division should become involved and the morale of the Mathematics Division collapsed. At first the Radio Division wasn't sure it wanted to be involved in the very odd design that Turing had invented but in August 1947 it was announced that a "pilot" ACE would be built. The Pilot ACE was essentially an extension of the test machine but this time it was really going to be built. The machine ran its first program in the May of 1950.

Pilot ACE

|

|||

| Last Updated ( Saturday, 07 June 2025 ) |