| Parentheses Are Trees |

| Written by Mike James | |||

| Thursday, 08 May 2025 | |||

|

Parentheses are at the heart of programming. Understand parentheses and you can rule the earth. No, seriously! Parentheses, trees and stacks are all interconnected in a very deep and fundamental way. Back in the early days of programming, long before Google started asking why manhole covers are round, one of the very common programming aptitude tests was to take a long mess of parentheses and ask the candidate if they were valid. Something like: Is:

a valid expression? So parentheses are fundamental to programming and being able to handle parentheses is a fundamental programming skill. But why? The simple reason why the humble parenthesis is so great is that it forms a tree structure as soon as you give it a chance. Hence the title - Parentheses Are Trees. The fact that parentheses are trees might not seem obvious so let's see how this works. A single parenthesis is a useless thing. It only comes into its own when paired with a parenthesis of the opposite handedness. The reason that a ( goes with a ) is simply that together they form a container. Put simply you can put something in between the parenthesis -

Usually the data that you put in the parenthesis has some sort of structure but this isn't really relevant to the key property of parenthesis. However even at this stage you can see that parenthesis can be used to represent an array:

What makes parenthesis really useful is that the data that you place between a pair of parenthesis can be another pair of parenthesis. This is always the moment when a simple data structure turns into a complex one - let a one dimensional array element store another array and the result is a two dimensional and more array. Letting a data structure store other data structures is one way of getting brand new things. If you allow a parenthesis pair to store another pair of parenthesis then the result is a tree. For example:

corresponds to a binary tree with two terminal nodes:

You can now construct examples as complicated as you care to make them. For example:

The nesting of parenthesis simply gives the structure of the tree that the parenthesis correspond to. Now you can see why many computer languages use a lot of parenthesis. Probably none more so than the infamous Lisp and at this point who could resist quoting the well known xkcd cartoon:

For more xkcd cartoons click here.

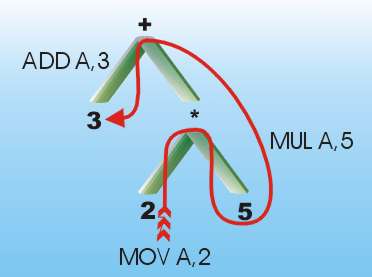

Lisp can get away with adding very little additional machinery to the parenthesis to create a complete and powerful language. The fact that parenthesis form a tree structure also explains the strange and arbitrary rules that you had to learn in school concerning arithmetic. The rule of arithmetic expressions form a "little" language the grammar of which can be expressed as a very simple tree structure with the rule that you always work out the expression by doing a left to right depth first walk. Consider the expression 3+2*5. To make sense of this and evaluate it correctly we have to invoke the idea of operator precedence. In particular we have to say that multiply has a higher precedence than addition so that the expression is 2 times 5 plus 3. However if this expression had been written as ((3)+((2)*(5))) then no operator precedence rules need to be used. The parenthesised expression corresponds to the tree:

and you can see that walking the tree in depth first either right to left or left to right and performing the operations indicated at each of the nodes gives you the correct evaluation. Here is a depth first left-to-right evaluation:

In other words if you are prepared to put all the parenthesis needed into the expression to make the syntax tree of the expression clear and unambiguous you don't need to introduce the idea of operator precedence. Of course we prefer to leave out parenthesis and complicate things by claiming that multiplication has to be done before addition. In fact we leave out so many parenthesis that we have to use the "My Dear Aunt Sally" rule - i.e. Multiplication and Division before Addition and Subtraction. Perhaps the biggest use of parenthesis today is in the form of all those markup languages that generate hierarchies i.e. trees of visual objects. For example what is HTML other than a bracketing syntax -

Just think of each open tag as a "(" and each closing tag as a ")". The same is true of XAML and all the other object instantiation languages. They all create tree structures. In a more general context XML is a bracketing system that generates general tree structures consisting of arbitrary data. For another example consider the nesting of control structures such as for, if, do, while and so on. These too are a bracketing language, often using curly brackets {}, and they generate a tree structure which the compiler has to work out to successfully parse the language. Once you notice the way bracketing generates hierarchies and general tree structures you start noticing them more or less everywhere. Perhaps now you will agree that parenthesis are fundamental to programming and testing the ability to work with them is probably a good way to see if some one is going to make the grade as a programmer. We have one question remaining - what arrangements of parenthesis are legal? The simple answer is only those arrangements that correspond to complete tree structures and there are only two ways in which a set of parenthesis can fail to do so. The first is just not having the same number of opening and closing parenthesis. You can't have half a container and so all valid bracketing structures have to match numbers of opening and closing parenthesis. This is a minimal condition for legal parenthesis. The second condition is that the pairs of parenthesis always occur in the right order - that is you always have () and never )(. Put as simply as this you would think that this condition is trivial but it is very easy to hide a pair of parenthesis in the wrong order. For example, ())(()() This structure is clearly wrong but there is no single answer to exactly what is wrong with it. For example you might say that it corresponds to any of the following groupings: () )( ()() In other words there is no single correct way to parse an incorrect structure. So how do we check for a valid bracketing structure? There is more than one answer to this but the simplest is to see if it is possible to walk the tree that the parenthesis describe. To do this you need a stack. All you have to do is scan the expression from left-to-right. Each time you encounter an opening parenthesis push it on the stack. Each time you encounter a closing parenthesis pop the top of the stack - if there is nothing on the top of the stack to pop then you have an invalid set of parenthesis. If you reach the end of the scan without trying to pop an empty stack then the stack will be empty if the expression was valid. For example in the case of:

the stack contents are:

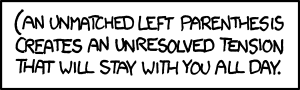

As the stack is empty when the scan is complete the expression was valid. The real question is can you see that this algorithm works? The answer is that the stack algorithm performs a depth-first left-to-right tree walk and this can only be completed if the parenthesis really do specify a tree. Notice that we are only considering parenthesis that are unlabeled - that is any closing parenthesis will pair with any opening parenthesis . Things become a little more difficult if you allow named parenthesis as in HTML, XML or program language structures. Then there are other ways to get things wrong such as <div><span></div></span>. You can easily modify the stack algorithm to detect such errors - all you have to do is make sure that the popped parenthesis matches the closing parenthesis that caused the pop operation. Parenthesis, stacks and trees go together perfectly. The final word however should go to xkcd and the observation in its blog of a halcyon time when Wikipedia had a sense of humor. The blog quotes from the Wikipedia article on parenthesis: Parentheses may also be nested (with one set (such as this) inside another set). This is not commonly used in formal writing [though sometimes other brackets (especially parentheses) will be used for one or more inner set of parentheses (in other words, secondary {or even tertiary} phrases can be found within the main sentence)] Sadly the Wikipedia entry no longer contains this paragraph... Yes parenthesises are fundamental to programming so much so that some programmers can spot a malformed structure instinctively. It is as if their eyes had a developed a co-processor for walking the tree structure. This perhaps the source for the final final word from parenthesis obsessed xkcd:

Only if you are a programmer...

Related reading:Javascript Data Structures - Stacks, Queue and Deque Stack architecture demystified The LIFO Stack - A Gentle Guide

To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, sign up for our weekly newsletter, subscribe to the RSS feed and follow us on Twitter, Facebook or Linkedin.

|

|||

| Last Updated ( Monday, 12 May 2025 ) |