| Taming Regular Expressions |

| Written by Nikos Vaggalis | |||

| Friday, 16 September 2016 | |||

Page 1 of 2 Despite their power, regular expressions come with their own challenges. First of all, they have a tendency to quickly become unreadable, so that understanding them becomes a matter of deobfuscation. Furthermore learning how to use them involves a steep curve as they've always been difficult to master. But first, let's take a deeper look into the domain specific problem that SRL tries to alleviate. To address the primary issue of unreadability, the /x modifier was introduced, which allowed for the inclusion of white space, line breaks as well as commenting in the regex itself. Under /x the regex engine wouldn't treat those elements as part of the expression to match, therefore allowing their use for the purposes of indentation and self-description. Under /x, becomes more readable and self-explanatory : However, the more elaborate the case, the more difficult to document : Source: Regular Expressions Cookbook Second Edition

This example matches any of the following seven strings, with any combination of upperand lowercase letters: • regular expressions Add language specific extensions like those of Perl described in Advanced Perl Regular Expressions - The Pattern Code Expression

/(??{

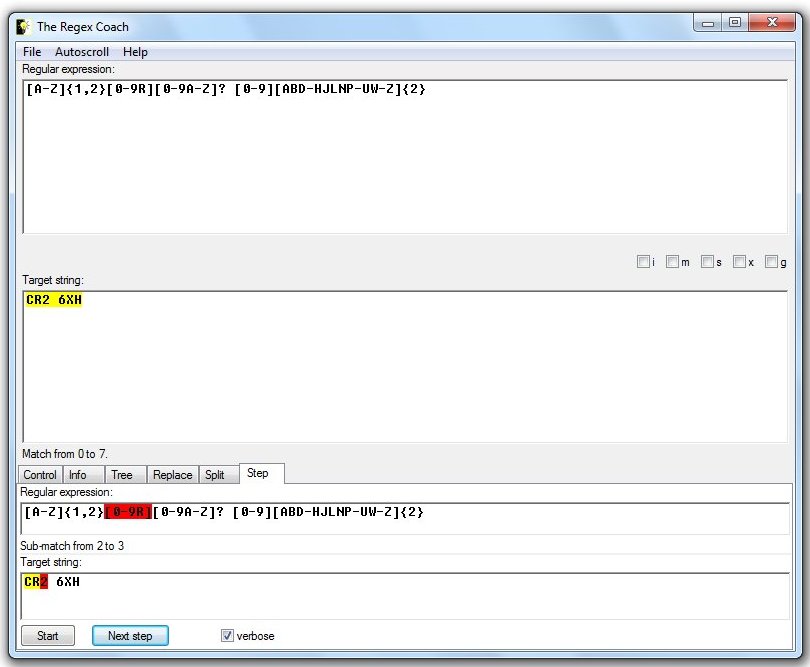

and the tasks of commenting becomes impossible! What about other problem of being the too difficult to master? There are a few techniques. The first is taking shape in the form of tools which consume the expressions and disassemble them in order to illustrate their inner workings. One such application is the Regex Coach:

Another takes shape in the form of libraries, the likes of Perl's YAPE::Regex::Explain, which try to explain the steps the engine undertakes in its attempt to find a match, in natural language:

[0-9][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z]{2}) (case-sensitive) (with . not matching \n) (matching whitespace and # normally):

----------------------------------------------------- (between 1 and 2 times (matching the most amount possible)) 'A' to 'Z' (optional (matching the

most amount possible))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- to 'H','J', 'L', 'N', 'P' to 'U', 'W' to 'Z' (2 times)

Both of them, however, are approaches deemed valid only after the regular expression has been constructed. As such they do not play any role. or offer any help. in the initial stage of trying to define the regex itself. An approach that goes the oposite way of an algorithm coming up with a similar or even better expression than its user could ever do, is found in the premises of Genetic Programming. We've already examined such an approach in Automatically Generating Regular Expressions with Genetic Programming, where the algorithm, initially assisted by the user by means of singling out the text segments looked for in matching, generates a suitable regular expression which can later on be used in code written in any programming language such as Java, PHP, Perl and so on. What's even more interesting is that this approach doesn't require familiarity with either Genetic Programming or the regular expressions syntax. So working. with this example, we need, from the following text, to match all numbers between 0 and 999999: 300000 1000000 2500000 400000000 22 0 1000 82468 73055 We start the algorithm by marking the candidate numbers: 300000, 22, 0, 1000, 82468, 73055 and let it come up with the following, matching regular expression: (?<= )\w\w?+\w?+\w?+\w?+\w?+(?= )|123456

This output can now can be used in our code for matching this pattern.

|

|||

| Last Updated ( Friday, 16 September 2016 ) |