| Copy protection and DRM |

| Written by Administrator | ||||

| Thursday, 13 May 2010 | ||||

Page 1 of 3 Copy protection, or Digital Rights Management (DRM) in general, is something that in most cases users hate and the entertainment industry really likes. When the audio CD first appeared the only way you could copy one was to tape and accept the loss of quality inherent in converting a digital recording to analog. There just were no low-cost CD recorders. Application CDs were also all-but-uncopiable, unless you had a CD pressing plant at your disposal! CD-RW drives changed all that and made it possible to make exact copies of audio as well as program CDs. The story was repeated with DVDs and DVD-RW drives and domestic DVD recorders and now it's the turn of Blu-ray. In an effort to try to return to the days when a CD, DVD or Blu-Ray disk was uncopiable, the entertainment and software industry has turned to increasingly sophisticated ways of implementing copy protection. None of this sounds amazing or even interesting from the technological point of view until you stop to think about it. A CD/DVD/Blu-ray disk is a digital recording and a CD/DVD-RW/Blu-ray drive is designed to create a 100% identical copy – a bit for bit digital copy literally every “bit” as good as the original. How can it be possible to implement copy protection that discriminates between the original and the copy when they are supposed to be identical? This is the problem that faces anyone wanting to invent a copy protection scheme and it seems impossible – so how does it work? The copy protection war is on going and as soon as one side invents a method the hackers find a way around it. This means that it isn’t possible to be precise how copy protection works because it is evolving all the time. There are essentially three approaches:

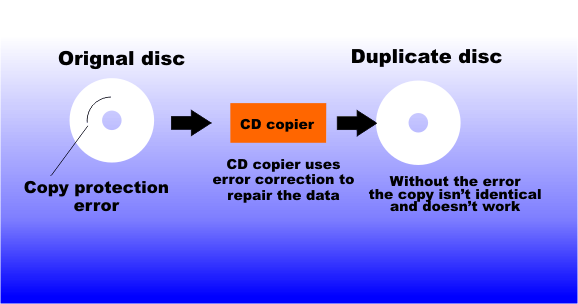

Lots of errorsCDs, DVDs and Blu-Ray disks only work as well as they do because of the use of sophisticated error correction. No disc is perfect and as it plays additional data is used to detect and correct errors. In each block of data, or frame, there are 24 data bytes, eight error correction bytes, a control and display byte and some packing bits to keep them all separated. In short not very much of a disc actually contains real data and one third of the recording space is used for error detection/correction data. The ratio is even higher for a DVD and blu-ray which has even more space allocated to error detection/correction. If you take a disc and put it through a copying process then any errors detected during reading are corrected in the usual way and the perfect reconstructed data is fed through to the disc being written. What this means is that the copied disc isn’t an exact copy of the original – it can be better than the original! Usually this is an advantage. If you have an audio CD that doesn’t work in a domestic player then a copy made using a PC will often play without problems. During the copying process the PC can take its time and re-read any data that contains errors until it gets it right and creates a duplicate that is better than the original.

A copy can be better than the original because error correction codes are used to remove errors. This results in a copy that isn’t the same as the original.

This “better than new” approach can also be turned into a copy protection scheme by simply including “correctable” errors that have to be there for the disc to function. This works well for CD/DVDs that contain software because it can be specially written to look for, and only work with, the errors on the disc. It doesn’t work with audio or video discs because domestic players correct the error and play just as well if it is there or not there. |

||||

| Last Updated ( Thursday, 13 May 2010 ) |