| Alan Sugar's PCW - The Commodity Computer |

| Written by Historian | |||

Page 1 of 2

The PCW storyThere is a fascination for computers, which causes people to build the fastest, the best and the most technologically advanced. There is a pleasure in designing a clever computer that is common to taking on and meeting any intellectual challenge. However computers are also tools that are used to complete other tasks. They are potentially as boring as a typewriter or office stapler and in many ways the people who want to use them in this way wish they were more boring!

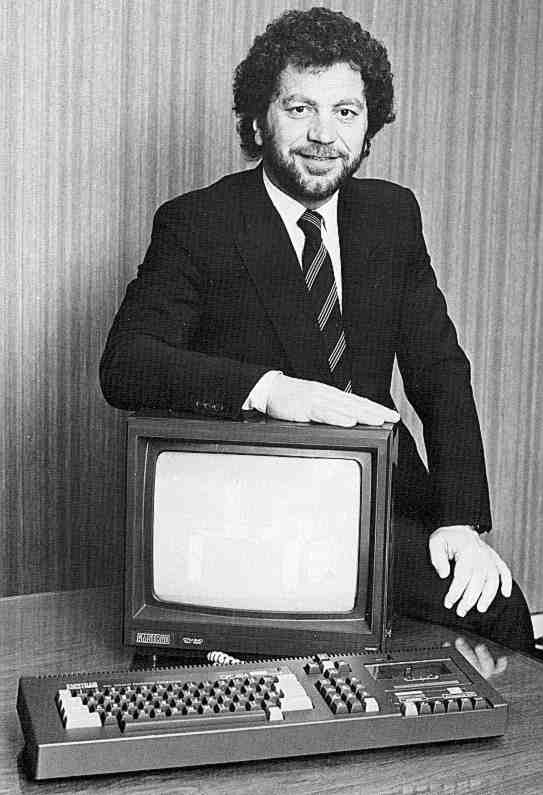

Alan Sugar, born 1947, London UK After the successful launch of the CPC464 Alan Sugar was sure that a good deal of Amstrad's future would be in computers, but this was a very different world to that of the hi-fi units that had fuelled the growth of the company. The computer companies that Amstrad would have to go up against in were also very different to the rough and ready Amstrad of the time. Business computer companies were ultra high tech and sold high tech products that cost thousands of pounds. Even the home-oriented computer companies like Sinclair were high tech and traded on the fact that the consumer saw them as "boffins" they could trust. Amstrad, on the other hand, sold products mostly to people who weren't interested in the technology – look and price were more important. Three months after Amstrad had launched the CPC, Alan Sugar was on route to Hong Kong with Amstrad's technical director, Bob Watkins. He asked for some paper to sketch on but all that was available was a contract with Digital Research that Watkins was reading. The contract was turned over and Sugar began to sketch out his ideas of their next computer. Sugar was following his instinct for integration leading to cost savings. In hi-fi he pioneered the "tower" system where amplifier, tuner, cassette deck etc were all built into one box. The advantage to the customer was simplicity. The advantage to Amstrad was that they could eliminate the duplicated power supplies, plugs and interfaces necessary between separate units. Sugar had already tried this approach when designing the CPC and it had worked well, but what was left to integrate into a new machine? The surprising answer was the printer! Alan Sugar had noticed one of the absurdities of the computer world. Printers were connected to computers via a very simple and standard interface. This interface forced the computer to send character codes to the printer, which then had to have the necessary processing power to convert these codes into shapes. The reason that this was absurd was that the computer already had the processing power to make the shapes necessary for the printer and indeed it had to do this to display results on the screen anyway. Just as once the video display had been a separate unit, a VDU, that had become integrated into the rest of the electronics it was now time to combine the printer with the computer. Sugar sketched a machine that had a screen, disk drive and printer all installed in a single case. The screen was to be turned through 90 degrees to give the display ratio needed for a sheet of paper. The printer was moulded into the top of the machine's case above the monitor. This made sure that the printer mechanism and paper feed were easy to get at. Bob Watkins immediately grasped the fact that this was a machine that could be built for less than the sum of its parts. The integrated printer needed virtually no processing electronics of its own and no interface. All it needed was the printing head and paper handling mechanism. The only problem was to work out what the machine would be used for. At that time home computers didn't come with printers and they often weren't even added as optional extras. A computer with a printer would make a natural word processor but specialized machines costing in the region of £10,000 dominated the market for word processors. As a home computer their new machine didn't seem attractive but if marketed as a word processor it might seem too limited. Sugar thought that if they could get the price down to around £400 then they might be able to attack the typewriter market. Instead of competing with the high-cost, high-quality, dedicated word processors Amstrad's new machine was to be a typewriter replacement – a real mass market product. Building the designIn July 1980 Sugar faxed MEJ Electronics with his design brief. MEJ had designed the CPC and was the obvious choice to design the next machine. In the meantime Sugar had found some low cost 3-inch disk drives and Orion, one of Amstrad's main subcontractors, were sure they could find some low cost printer mechanisms. This made it seem even more likely that the price of the machine could be kept down. Sugar made seven points concerning the design – it should have no colour or sound, there was to be an integrated printer, one power supply, one floppy disk and the word processing program in ROM, it should ignore all industry standards as it was to be a self contained unit., custom logic arrays were to be used as much as possible to cut the component count and a green, 80-column screen was specified. As things turned out not all of Sugar's original concept could be retained in the final design. The A4 size screen was simply too expensive and a conventional 80 by 25 line green on black display was adopted. It was also discovered that having the printer mounted on top of the monitor caused it to overheat. The solution was to make the printer a separate unit but it was very small, contained virtually no electronics and took its power from the main box. This makes the PCW sound like a machine that was more or less designed by Alan Sugar. True enough the concept was his but implementing the machine was still far from easy or straightforward. For example, the idea of placing the word processor into ROM was a very radical one and involved incorporating a CP/M compatible filing system as well. Of course the machine was going to use the same Z80 processor that the CPC used and this was to be a cause of much criticism by the technological elite. At the time the cutting edge processor was the 8086 and the change from an 8-bit world to a 16-bit world was in full swing. Anything that used an obsolete 8-bit Z80 processor was itself courting obsolescence. Except of course that Alan Sugar didn't care what powered the machine as long as it worked and he believed that this was going to be the predominant attitude of his customers. <ASIN:023074933X> <ASIN:1844547027> <ASIN:0132091984> |

|||

| Last Updated ( Thursday, 19 September 2019 ) |