| Vannevar Bush - The Man Who Didn't Invent The Computer |

| Written by Historian | ||||

Page 2 of 3

Towards the Differential AnalyzerThe first steps Bush took into the world of computing were taken because of the need to solve equations, a recurring need that drove computer development at the outset. The equations Bush wanted to solve related to power line transmission. This was a big problem back in the early days of electrification where exactly how electricity could be transmitted over long cables was a practical concern and the differential equations that took months to solve. Bush decided that a quicker route to the solution was an analog computer. The MIT electrical engineering department spent the best part of 20 years on the project! Bush first suggested the idea in 1925 and his students worked on the problem. They jointly invented an electromechanical multiplier and integrator.

By 1928 they had a very basic machine working and this proved that is was possible. Bush had lots of help with ideas from his students and it does seem that it was a joint invention but there is no doubt that it would not have worked without Bush guiding the project. At each step he attempted to replace mechanical components with electromechanical ones. At the end of 1928 he had funds to build an even larger machine. This was a big machine - almost as big as a digital machine. It had servo mechanisms where possible to make the mechanical components more accurate. This is the machine that Douglas Hartree saw and copied back in Manchester - only he used Meccano on a budget of £20.

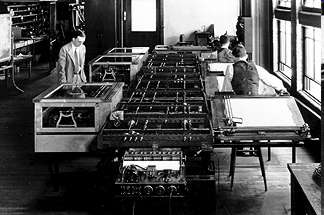

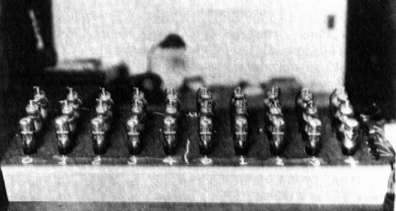

The complete Differential Analyzer Today we think of the MIT Differential Analyser as a number cruncher of a very specific and technical nature but at the time it was hailed as the first “thinking machine”. The New York Times ran an article with the headline “Thinking Machine Does Higher Mathematics”. In 1936 Bush delivered a paper to the American Mathematical Society entitled 'Instrumental Analysis'. It discussed the work of Charles Babbage and his attempts to build an analytical engine. Bush thought that by linking together some IBM punch card machines under the control of a central programmer he could build a close approximation to Babbage's machine. It was clear that Bush had understood Babbage’s work and the idea of programmability. Rapid Arithmetic MachineSoon afterwards Bush started to work on an electronic digital machine called the Rapid Arithmetic Machine. There is evidence that he documented the design in a series of papers written between 1937 and 1938 but no trace of these can be found. The machine was based on paper tape storage. It used three paper tapes - one for the data, one for the program and one as a sort of ROM. The program tape would be read repeatedly to carry out operations on each item of data on the data tape. There was apparently no suggestion that the program would use numerical addresses, nor was their any provision for conditional branching. Given the lack of detailed information, it is difficult to be sure exactly how it would have worked. If the machine had been finished then the need for some of these facilities would have become apparent as soon as it started work on real problems! All the registers, logic and arithmetic units were electronic and were built using vacuum tubes. It is difficult to be sure how much of the machine was built. They certainly built modules to prove the various designs needed for a working computer. A counter - part of the Rapid Arithmetic Machine The design was decimal and the counters and registers all used ten-state storage rings. To store a single bit in a binary machine you only need a two-state device. To store a digit in a decimal machine you needed a ring of ten vacuum tubes which automatically turned on and off in sequence - so counting from 0 to 9.

A decimal ring counter for the Rapid Arithmetic Machine In 1940 Bush estimated that the machine would be able to multiply two six-digit numbers in about .2 seconds and would run at a clock speed of .01MHz. A lot of time was spent trying to devise gas filled vacuum tubes to reduce the component count and then the work just stopped. The reason was that the design team was claimed for the Manhattan Project and work on the atomic bomb. War WorkDuring the war Bush headed the National Defence Research Committee (NDRC), a federal government agency to coordinate scientific research and the requirements of defense mobilization which Bush himself had proposed. This controlled the work of 30,000 scientists on research projects from the simple right up the development of the atomic bomb. Among the crucial inventions Bush was involved with. and for which he set up the Radiation Laboratory at MIT, were the cavity magnetron for detecting submarines and the SCR-584 radar, a mobile radar fire control system for anti-aircraft guns and a proximity fuze, a fuze inside an artillery shell that would explode when it came close to its target. In 1941 President Roosevelt established the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) and appointed Bush as its director. The OSRD was on a firmer financial footing than the NDRC since it received funding from Congress, and had the resources and the authority to develop weapons and technologies with or without the military. It also had a broader mandate than the NDRC, moving into additional areas such as medical research and the mass production of penicillin and sulfa drugs. The organization grew to 850 full-time employees, produced between 30,000 and 35,000 reports and was involved in some 2,500 contracts worth in excess of $536 million. In his role as director of the OSRD Bush played a pivotal role in the development of the atomic bomb, something he was proud of. In "As We May Think", an essay published by the Atlantic Monthly in July 1945, Bush wrote: "This has not been a scientist's war; it has been a war in which all have had a part. The scientists, burying their old professional competition in the demand of a common cause, have shared greatly and learned much. It has been exhilarating to work in effective partnership." With OSRD being wound up after the war, Bush argued that basic research was important to national survival for both military and commercial reasons, requiring continued government support for science and technology. In Science, The Endless Frontier, a July 1945 report to the president, he maintained that basic research was "the pacemaker of technological progress", writing: "New products and new processes do not appear full-grown, they are founded on new principles and new conceptions, which in turn are painstakingly developed by research in the purest realms of science!" Although it took until 1950 to become established, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the indeptdent agency that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering is seen as Bush's legacy. |

||||

| Last Updated ( Thursday, 08 August 2024 ) |