| World's Oldest Digital Computer Works Again |

| Written by Sue Gee | |||

| Tuesday, 20 November 2012 | |||

|

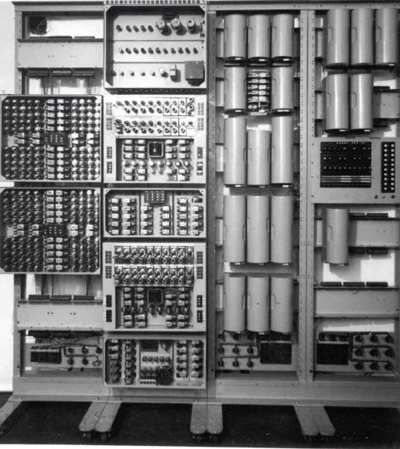

After a three-year restoration project, a 61-year-old computer known as the WITCH that features 828 flashing dekatron valves, 480 relays and a bank of paper tape readers, clatters back into action today at the UK's National Museum of Computing. The Harwell Dekatron was originally built between 1949 and 1951 to help atomic scientists at the UK Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) in Harwell, Oxfordshire. Its task was to perform complex calculations that were previously done by human mathematicians called "hand computers".

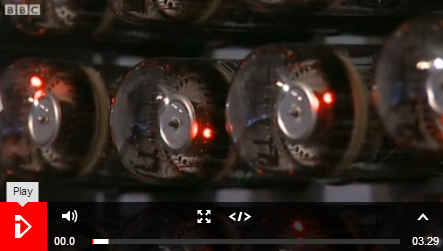

It had the distinction of being a digital, rather than a binary computer, and used dekatrons for volatile memory and paper tape for input and program storage. A dekatron is ten state storage device consisting of ten wires arranged in a circle in a neon tube. Only one of the ten wires supports a neon discharge at anyone time. A pulse on the transfer wire moves the discharge to the next wire either clockwise or anticlockwise - hence the characteristic circling light pattern. Dekatrons were used mostly to build decade counters in scientific devices such as Geiger and particle counters and are very characteristic of a particular era of electronics and physics. By 1957, the computer had become redundant at Harwell, but a scientist at the atomic establishment arranged a competition to offer it to the educational establishment putting up the best case for its continued use. It was won by Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College, which led to it being renamed the WITCH (Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computation from Harwell).

Photo: (c) Express and Star of Wolverhampton The WITCH as a teaching tool in the 1960s The WITCH was used by the college for computer education until 1973 after which it went on display to be public in the Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry. When that museum closed it was dismantled and put into storage. Luckily it was rediscovered in 2008 by computer conservationist Kevin Murrell when, by chance he noticed the control panel of the machine that he remembered from museum visits as a teenager in a photo of stored equipment and the various components of the computer was transferred to the National Museum of Computing (TNMOC) so that it could once again be put to educational use. As Kevin Murell explains: "To see it in action is to watch the inner workings of a computer -- something that is impossible on the machines of today. The restoration has been in full public view and even before it was working again the interest from the public was enormous." Delwyn Holroyd, a TNMOC volunteer who led the restoration team, said: "The restoration was quite a challenge requiring work with components like valves, relays and paper tape readers that are rarely seen these days and are certainly not found in modern computers. Older members of the team had to brush up on old skills while younger members had to learn from scratch!" (click for larger image) The WITCH is indeed unlike anything we regard as a computer. We now evaluate computers in terms of their speed and appreciate the fact that they become ever lighter and smaller. The Harwell Dekatron weighs 2.5 tonnes and was slow even by 1950's standards with a multiplication time of between 5 and 10 seconds. Indeed it was so slow that one of its original users at AERE, Bart Fossey ,who will be present at TNMOC for the switching on ceremony, attempted to beat it in a race. Using his desk calculating machine he kept pace with it for about half an hour working flat out but once he was exhausted the machine just kept going. Two of the computers original designers, Ted Cooke-Yarbrough, Dick Barnes, will also be present at TNMOC to witness their machine in action again. Cooke-Yarbough wrote in 1953: "a slow computer can only justify its existence if it is capable of running for long periods unattended and the time spent performing useful computations is a large proportion of the total time available". Luckily it proved to have this quality. It averaged 80 hours per week running time and was highly reliable. According to Dr Jack Howlett, Directory of the Computer Laboratory at AERE 1948–1961: It could be left unattended for long periods; I think the record was over one Christmas-New Year holiday when it was all by itself, with miles of input data on punched tape to keep it happy, for at least ten days and was still ticking away when we came back. The fact that the machine is still able to keep going at the flick of a switch is further testament to its durability. Watch this BBC video to see, and hear, it in action and Kevin Murrel and Delwyn Holroyd account of its restoration. BBC Video Official TMOC video

Dekatrons in action

More InformationRelated ArticlesFlossie - A Working Computer from the 1960s Award Established for Computer Conservation

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info

To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, install the I Programmer Toolbar, subscribe to the RSS feed, follow us on, Twitter, Facebook, Google+ or Linkedin, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

|

|||

| Last Updated ( Thursday, 22 November 2012 ) |