| Right On The Button - New Ways To Press |

| Written by Mike James | |||

| Monday, 26 March 2018 | |||

|

Buttons they are the "hello world" of the UI and yet we know little about how users interact with them. OK yes, we know that they click them or tap them or whatever, but how should a button respond to the human interaction? Researchers at Aalto University, Finland, and KAIST, South Korea decided to look into the humble button press and it turns out it is more of a psycho physical challenge than you might think. Professor Antti Oulasvirta at Aalto University, who is co-author of three papers that will appear in the Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2018, explains: "We push a button on a remote controller differently than a piano key. The press of a skilled user is surprisingly elegant when looked at terms of timing, reliability, and energy use. We successfully press buttons without ever knowing the inner workings of a button. It is essentially a black box to our motor system. On the other hand, we also fail to activate buttons, and some buttons are known to be worse than others." In case you are wondering - touchbuttons we're looking at you. It has been long known that touch screen simulated buttons are much more difficult to use than mechanical buttons. With a new theory of how mechanical buttons are used by humans could give us better buttons - even better touch buttons. The theory is there is a probabilistic model: The brain learns a model that allows it to predict a suitable motor command for a button. If a press fails, it can pick a very good alternative and try it out. That is the brain monitors the way a button is pressed an modifies it to increase the probablity of a sucessful press. The brain tunes the motor command to optimize the button press. To investigate this very general idea the researchers built a simulator to explore the way we push buttons.

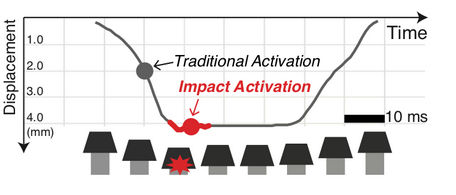

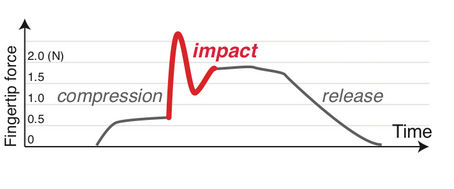

The key finding is that buttons should use impact activation. Instead of activating the button at first contact the button should activate at the point of maximum impact.

In practice this approach was 94% more precise in rapid tapping and 37% more accurate than a regular touch button. Of course, the problem is that you can't modify the activation point on a standard mechanical keyboard, but you can do this for a touch button. The reason that this works is that the feedback in terms of fingertip force is much bigger and more precisely located at the impact point: This probably allows the brain to more easily correlate the activation time with the motor profile. This also probably explains why the best keyboard I have ever used was the mechanically actuated Selectric typewriter. In this case the keyboard activaly drove the key down when it was pressed. I have wondered why this worked, but it fits in with the theory as the mechanical depressing of the key would produce an even larger feedback, but this time a negative fingertip force.

More InformationNeuromechanics of a Button Press Impact Activation Improves Rapid Button Pressing Moving Target Selection: A Cue Integration Model Related ArticlesWhy Touch Screens Are Terrible For Games And What To Do Button Feedback With An Electric Arc A Slap In The Face - A New UI? Passive Haptic Learning - The No Effort Way To Learn A sticky touch screen improves interaction

To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, sign up for our weekly newsletter, subscribe to the RSS feed and follow us on Twitter, Facebook or Linkedin.

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info

|

|||

| Last Updated ( Tuesday, 27 March 2018 ) |