| The Virtual Evolution Of Walking |

| Written by Mike James | |||

| Wednesday, 22 January 2014 | |||

|

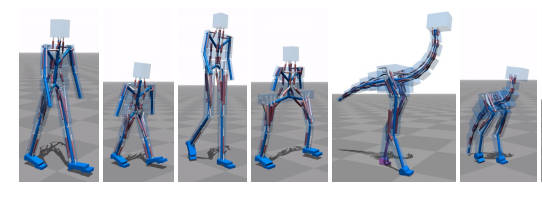

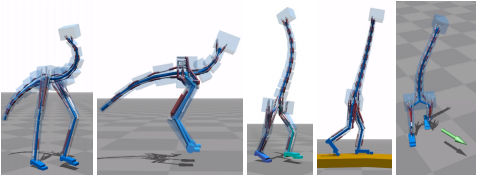

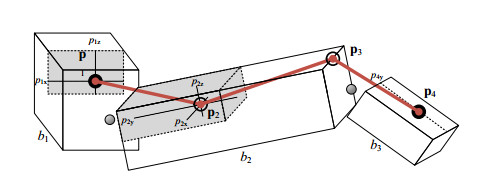

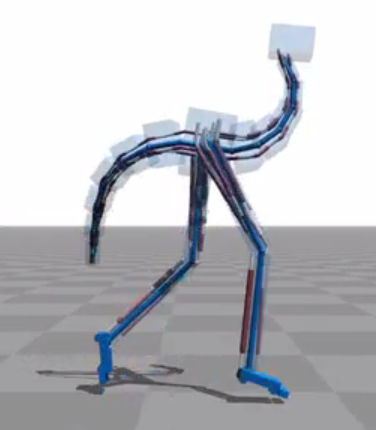

Simulated bipedal creatures can learn to walk naturally without any input as to how they should do it. They even learn to adopt different gaits according to the speed they are trying to move at. The technique is simple in theory but the difficulties are in the detail. A new video of a variety of virtual creatures learning is fun to watch as they slowly evolve and fall over. A very much cheaper way of testing out robotic walking algorithms is to use a physics simulator - then real things don't break when there is a failure and the creature falls over. This approach has a long history but the latest effort, from a group of Dutch researchers and outlined in Flexible Muscle-Based Locomotion for Bipedal Creatures deserves some attention because it seems to be effective and doesn't require any input data about how to walk. Take a simulated skeleton and attach a set of biologically inspired simulated muscles - both in full 3D, The muscles even have a neural delay included in all feedback paths. The arrangement of the muscles, the muscle routing, isn't fixed and it and it is part of the optimization along with the muscle control systems. This is a bit like evolving the muscle arrangement that works best with a given skeleton.

So, for example, you can take a skeleton that has broad hips and one that has narrow hips and the muscle arrangement will be modified from a basic starting arrangement to make the locomotion efficient. If you watch the video of the different creatures that the method has been tried out on you will see that it seems to work. It does generate bipedal gaits that look natural.

The details of the control system are fairly complicated but there are a set of target features involving positions of the head , trunk and leg segments. A dynamic model is used to work out a set of muscle torques and hence excitations that will move the body from its current state to one of the target positions.

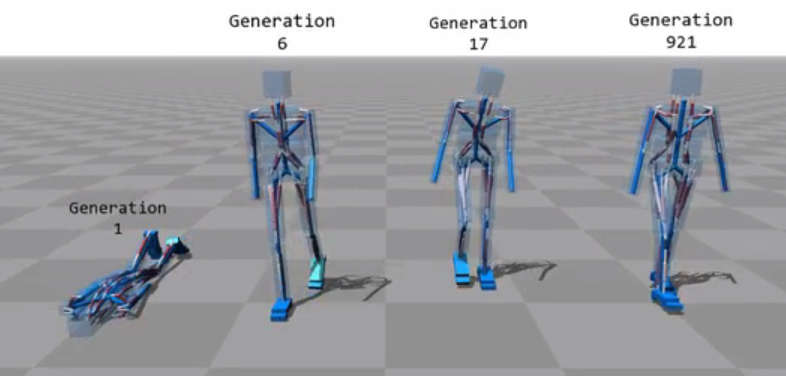

To obtain the optimum control and muscle routing, the performance of the creature is measured taking into account speed, pose, and effort. The optimization was performed offline using an evolutionary algorithm. To see how this all worked simply watch the video.

The optimization is performed using Covariance Matrix Adaptation, which is worth knowing about. First an initial population is generated with random settings sampled from a Normal distribution with unit covariance matrix. Next the creatures in the population are tested and rated according to their fitness. A small sample, 20 in this case, of the fittest members of the population are extracted and the mean vector and covariance matrix of this "survivor" group is computed. The next generation is created using a Normal distribution with the survivor mean vector and a covariance matrix proportional to the survivor covariance matrix. This is a stochastic version of gradient decent and it finds the optimum parameters in this case in anything from 2 to 12 hours on a desktop PC with 500 to 3000 generations.

What is interesting about this approach is that it doesn't use any captured motion data to create the bipedal locomotion - just the biologically inspired creatures and their physiology and the physics. Can this be made to work with real bipedal robots? My guess is that roboticists probably wouldn't throw boxes at the likes of Atlas.

More InformationFlexible Muscle-Based Locomotion for Bipedal Creatures (pdf)

Related Articles

To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, install the I Programmer Toolbar, subscribe to the RSS feed, follow us on, Twitter, Facebook, Google+ or Linkedin, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info

|

|||

| Last Updated ( Wednesday, 22 January 2014 ) |